Last fall, a hydroelectric dam in Tajikistan, the government of Portugal and a cruise-ship operator all issued debt at unusually low interest rates. The seemingly unconnected deals are part of a proliferation of aggressive bond sales influenced by a decade of loose monetary policy and a demographic shift in global investing.

Historical limits on who can borrow, and at what cost, have broken down as fund managers agree to previously unpalatable terms.

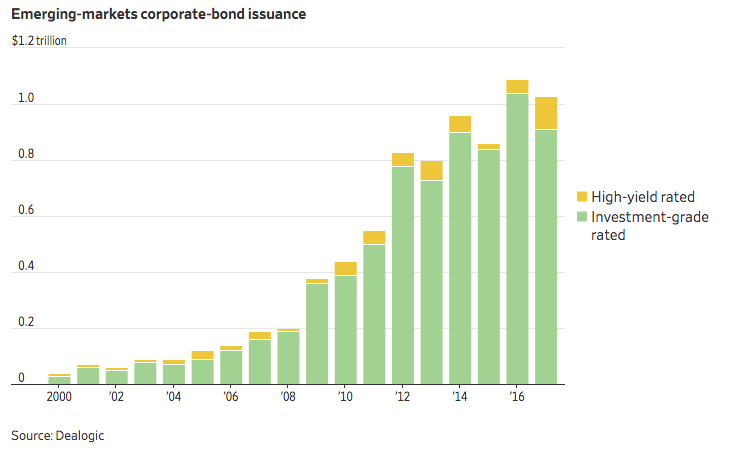

Central bankers in the U.S., Europe and Japan helped shape the new breed of deals by simultaneously purchasing over $1 trillion in high-quality bonds since 2009 and lowering benchmark interest rates to jump-start their faltering economies. Modest economic growth came, but the strategy crowded private investors out of safe debt, prompting them to buy riskier bonds to boost returns.

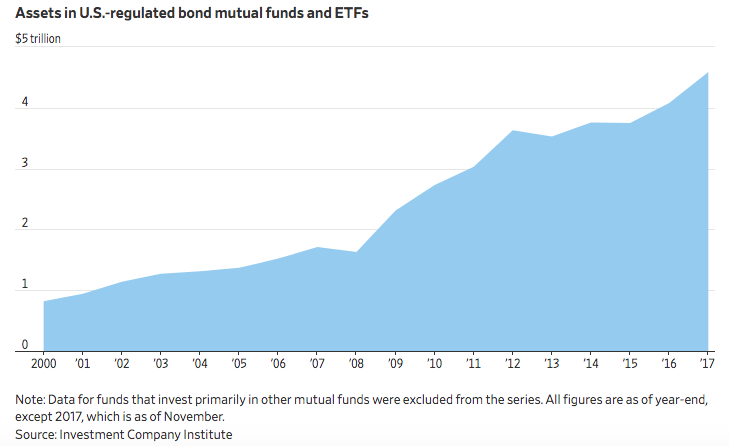

Retiring baby boomers amplified the trend by moving their investments away from stocks into bonds, boosting assets in U.S. bond mutual funds to $4.6 trillion in November from $1.5 trillion a decade earlier, according to the Investment Company Institute, a trade group for investment firms.

“A lot of smart people say we’re in a bubble, and their fingers are pointed at credit,” said Steven Shenfeld, president of MidOcean Credit Partners, an investment firm focused on high-yield debt. MidOcean is preparing for the expected downturn in certain portfolios by placing bets that will pay out if bond prices sell off, he said. “I’m just an old trader that’s seen this movie too many times.”

U.S. bond yields ticked up this year but remain below historical averages, and investors keep buying below-investment-grade bonds, squeezing the risk premium junk bonds pay over Treasurys to a 10-year low. Some central banks are now reeling back quantitative easing to keep economies and markets from overheating. An anecdotal gauge of five key markets—emerging markets, municipal bonds, government debt, securitizations and corporate loans—shows temperatures are plenty hot already.

Here are some tales from the bleeding edge of credit:

Soviet dream…

Tajikistan is ranked one of the world’s most corrupt countries by Transparency International. When the country sold its first international bond in September, offering documents warned that “corruption, and allegations of corruption, in Tajikistan may have a negative impact on Tajikistan’s economy.”

Tajikistan is ranked one of the world’s most corrupt countries by Transparency International. When the country sold its first international bond in September, offering documents warned that “corruption, and allegations of corruption, in Tajikistan may have a negative impact on Tajikistan’s economy.”

So many investors wanted a piece of the $500 million deal that Tajikistan was able to negotiate a significant reduction in the interest rate of the bond.

Cash raised in the sale is earmarked to finish construction of the Rogun hydroelectric dam, begun in 1976 under the Soviet Union, and repayment of the debt is projected to come from electricity sales to Afghanistan and Pakistan. Conflict in Afghanistan “could have a material adverse effect on Tajikistan’s economy and its ability to make payments on the notes,” the bond offering said.

Tajikistan’s investment bank, Citigroup Inc., initially marketed the bond to yield 8% but received so much investor demand the clearing price was cut to 7.1%. The bonds still paid well above the 5.4% average yield for emerging-market debt in September, according to an index maintained by JPMorgan Chase & Co, making them attractive to yield-hungry bond funds. Buyers included large U.S. asset managers like Fidelity Investments, which purchased $14 million of these bonds for its mutual funds, regulatory filings show.

A spokesman for Citigroup declined to comment. Officials from Tajikistan’s Ministry of Finance couldn’t be reached for comment.

…American Dream

…American Dream

Another languishing development, the American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, N.J., also got a jump-start from bond markets in 2017. The project, previously known as Xanadu, broke ground in 2003 but ran out of money to finish construction. The mall’s current owner—its third—is betting that it can buck the trend of retail extinction spreading across the country.

Another languishing development, the American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, N.J., also got a jump-start from bond markets in 2017. The project, previously known as Xanadu, broke ground in 2003 but ran out of money to finish construction. The mall’s current owner—its third—is betting that it can buck the trend of retail extinction spreading across the country.

Initial efforts to fund the mall- and-amusement-park-hybrid with real-estate loans foundered during the financial crisis. Canadian developer Triple Five took over the project in 2013 and announced plans to sell municipal bonds but that stalled under political opposition and pushback from skeptical investors.

Goldman Sachs sold the tax-exempt bonds in June at yields as high as 6.9%, depending heavily on one investor: John Miller, a portfolio manager at Nuveen Asset Management LLC, whose largest mutual fund has more than doubled in size since 2014 to about $17 billion. Mr. Miller bought half the American Dream bonds, or about $570 million, because of the yield and because the project will flourish, he said. Unlike most malls, American Dream will derive most of its revenue from experiential attractions that can’t be replicated online, rather than depending on retailers, he said.

Portugal Undercuts Uncle Sam

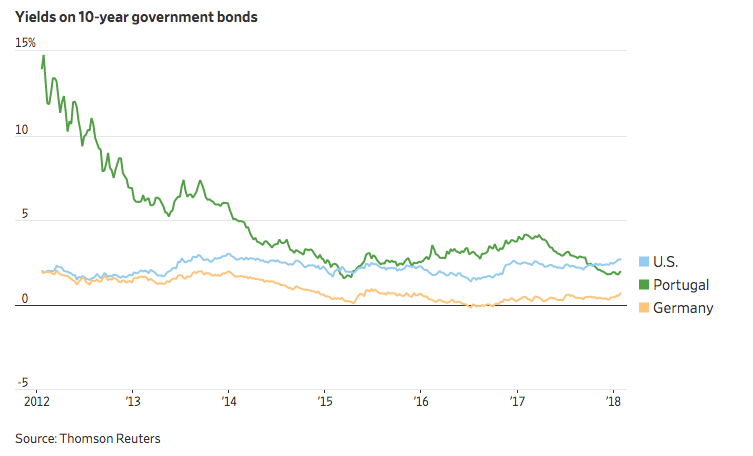

On Nov. 8, Portugal auctioned €1.25 billion ($1.55 billion) of 10-year bonds to yield 1.94%—the lowest rate ever for the country. Portugal needed an international bailout in 2011 and still has a junk credit rating. Investors placed bids for about €2 billion of bonds, far exceeding the amount on offer.

On Nov. 8, Portugal auctioned €1.25 billion ($1.55 billion) of 10-year bonds to yield 1.94%—the lowest rate ever for the country. Portugal needed an international bailout in 2011 and still has a junk credit rating. Investors placed bids for about €2 billion of bonds, far exceeding the amount on offer.

Portugal remains one of the most heavily indebted countries in Europe, but the auction set its borrowing cost below that of the U.S. government, which sold 10-year bonds in November to yield 2.31%. The U.S. has a triple-A credit rating and is viewed as one of the safest borrowers on the planet.

The gap partly reflects differing inflation rates in the eurozone and the U.S., said Paula Ramalho, a Portuguese Treasury official.

The mismatch is an unintended consequence of the European Central Bank’s use of low interest rates and bond purchases to revive economic activity. The policy resulted in negative bond yields in the eurozone’s strongest economies like France and Germany, forcing bond funds to buy more in riskier countries like Portugal to deliver positive returns.

Bonds Are a Diamond Dealer’s Best Friend

Bonds Are a Diamond Dealer’s Best Friend

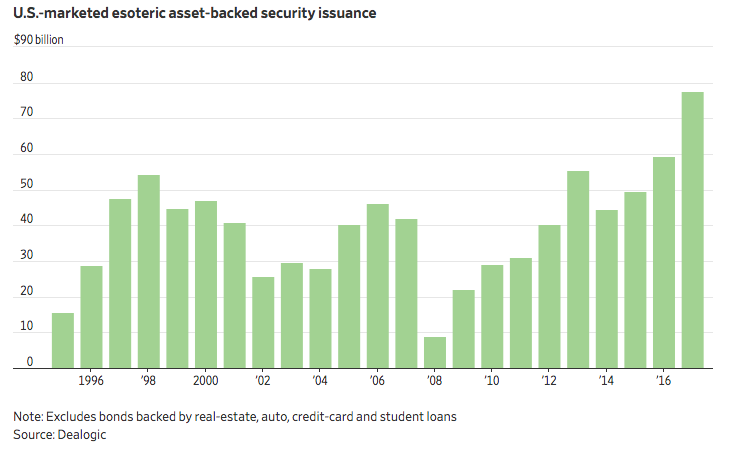

Asset-backed securities: These three words are redolent of the risk taking, financial alchemy and hubris that fed the credit crisis. Mortgage-backed bonds were the most infamous ABS, but investment banks innovated far stranger types, including airplane-backed bonds, bonds backed by royalties owed to David Bowie and, in 2007, a $100 million bond backed by the inventory of Antwerp, Belgium-based diamond dealer Diarough.

Asset-backed securities: These three words are redolent of the risk taking, financial alchemy and hubris that fed the credit crisis. Mortgage-backed bonds were the most infamous ABS, but investment banks innovated far stranger types, including airplane-backed bonds, bonds backed by royalties owed to David Bowie and, in 2007, a $100 million bond backed by the inventory of Antwerp, Belgium-based diamond dealer Diarough.

Like many precrisis ABS, repayment of the diamond bonds was predicated on refinancing, and after the securitization market dried up, Diarough restructured the debt instead. The gem merchant cut the interest it paid bondholders and extended the due date of the bonds, according to a report by Moody’s Investors Service.

By 2017, the esoteric ABS market was showing signs of life again, and Diarough returned with a $150 million deal in August. Bond funds, flush with cash from yield-hungry investors, flocked to the new bonds, warranting an increase to $155 million. The Pioneer Bond Fund, which has about doubled in size since 2015 to $5 billion, bought $4.2 million of the Diarough bond, according to a regulatory filing.

Gert Ovart, a finance manager at Diarough, declined to comment. Officials at Pioneer couldn’t be reached for comment.

Cruise Ship Limbo Party

Cruise Ship Limbo Party

Executives of Miami-based Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings gathered in their boardroom in October to toast an unexpected accomplishment with Veuve Clicquot. They had negotiated a $375 million bank loan for the company at an interest rate of about 3%, the lowest in its 55-year history.

Executives of Miami-based Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings gathered in their boardroom in October to toast an unexpected accomplishment with Veuve Clicquot. They had negotiated a $375 million bank loan for the company at an interest rate of about 3%, the lowest in its 55-year history.

It is also one of the lowest yields ever achieved by any borrower in the so-called leveraged loan market for companies with below-investment-grade credit ratings. “We’re told this is the cheapest [rate] ever for a credit of our quality,” said Howard Flanders, treasurer of double-B rated NCL

The force driving the race to the bottom in leveraged loan rates is the same one causing the feeding frenzy in other credit markets: Investors reaching further for yield in response to central bank policy. With most triple-A Treasury bonds paying negligible yields, banks and insurers from Tokyo to New York are buying more investment-grade corporate and securitized bonds to boost returns.

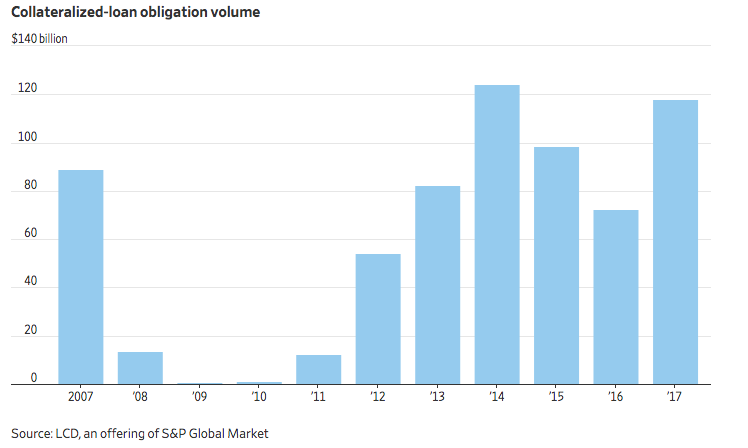

That has benefited managers of collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, who issue triple-A bonds and use the borrowed money to buy up bundles of leveraged loans like those borrowed by NCL. No surprise, CLO issuance boomed in 2017, boosting demand for corporate loans and giving NCL unprecedented pricing power and a new reason to break out the champagne.